Economists have settled on Slovenia as the next euro problem country. Small, with an estimated GDP of $45.6 billion in 2012, Slovenia immediately calls to mind the last failing euro-zone country to dominate headlines: Cyprus. Whether or not that is an apt comparison, Slovenia is on the brink.

What’s the problem with Slovenia?

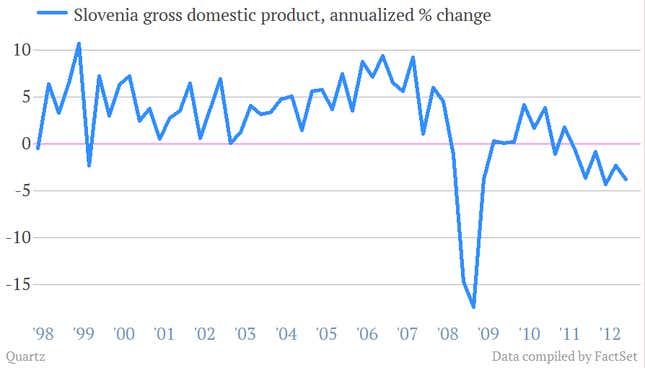

Slovenia experienced a dramatic boom and a continuing bust. In the run-up to its joining the euro in 2007, the country’s economy sharply expanded… only to burst under the weight of the financial crisis.

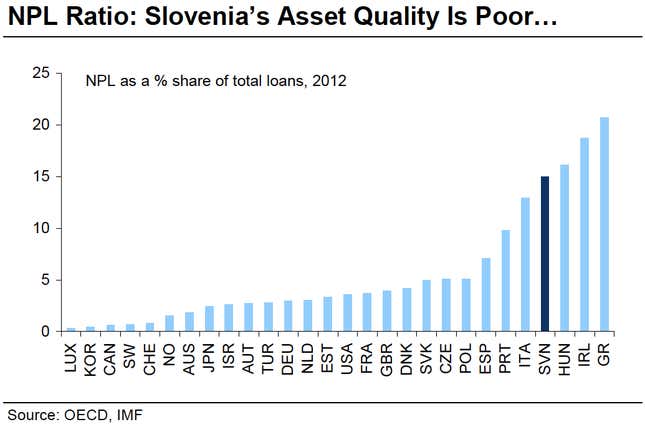

Most affected are the banks, the largest of which are owned by the Slovenian government. About 20% of loans on average are non-performing, by Morgan Stanley’s definition, which essentially means that the borrowers are very behind in making payments on them. As many as 35% could be non-performing at state-owned banks.

“Our proprietary stress test suggests a €2.2-3.4 billion capital need for Slovenian banks, equivalent to 6-10% of GDP,” writes Morgan Stanley analyst Francesca Tondi. By contrast, Cypriot banks’ €10 billion recapitalization equaled 43.5% of its 2012 GDP.

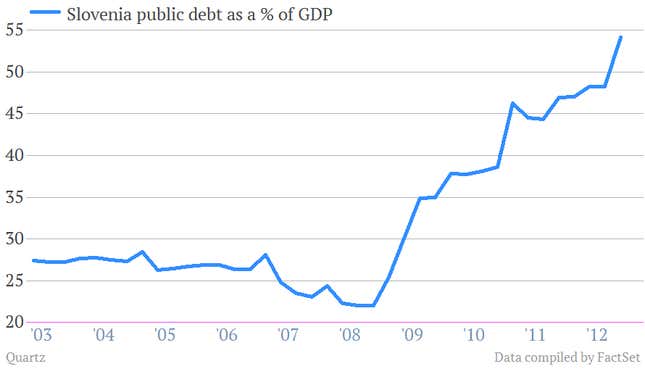

Concerns about the quality of bank assets have made it harder for the Slovenian government to fund its borrowing. Although still one of the lowest in the euro area, its ratio of public debt to GDP has grown quickly, nearly tripling since 2008. Moreover, it’s a good deal higher if you take into account state guarantees of bank assets, which could be worth more than 25% of GDP, according to Morgan Stanley.

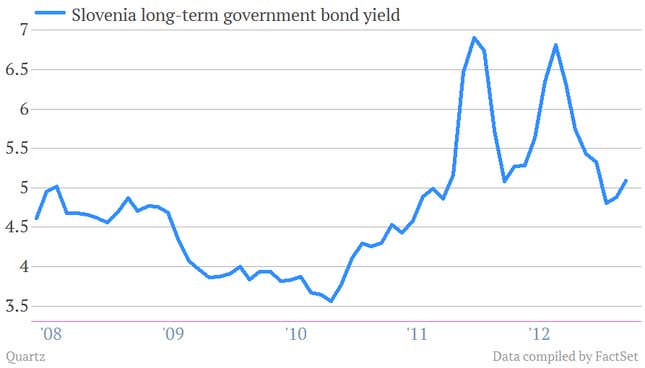

Thus yields on Slovenian government bonds—which reflect the government’s likelihood to repay its debts—have been inching upwards. Last week, Slovenia called off a bond sale when Moody’s downgraded the country’s long-term credit rating to “junk” or sub-investment grade. It later sold €3.5 billion in government bonds, with 10-year bonds yielding 6%. Even so, the recent bond sales raised enough money to fund government borrowing through the end of the year.

Data on the graph below are averaged monthly—and the most recent data are for late March—but it’s clear that bond yields for Slovenia jump along with weakness elsewhere in the European periphery.

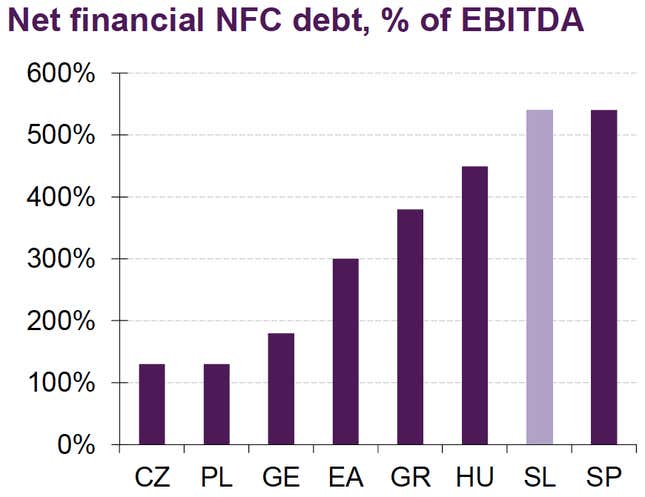

Non-financial companies (NFCs) are also very highly leveraged in Slovenia compared to other euro-zone countries, particularly as a share of their earnings. This suggests that corporations are vulnerable when credit contracts.

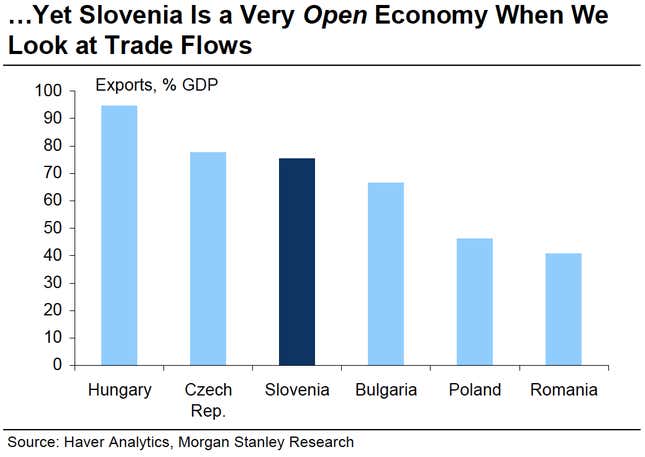

Slovenia does have one really positive data point on its side, however: exports. High demand for exports suggests that Slovenian products, not to mention Slovenian tourism, are competitively priced. More than half of its goods ship to other countries in the euro area. Italy buys 12% of the country’s exports, and Germany accounts for 20%.

So what can Slovenia do?

First, the country intends to announce by the middle of this month plans to cut government spending, raise taxes, and privatize many of its most important industries. Political squabbling between the country’s central bank and finance ministry could obstruct these reforms, however. The country’s parliament also voted on May 7 to put off some of the most difficult decisions on fiscal consolidation until later in the month.

Slovenia is also about to spell out plans to form a so-called bad bank, titled the Bank Asset Management Company (BAMC), that will absorb the bad loans on banks’ balance sheets. Morgan Stanley’s European economic team estimates that there are approximately €7-8 billion in bad loans in the country’s banking system, but it’s not clear which banks will funnel bad assets into that bad bank. It’s also not clear how much funding the bad bank will have and where it will come from. The country hopes to start moving assets to the bad bank by June.

Then, in late July, Slovenia will recapitalize state-owned banks.

Is Slovenia the new Cyprus?

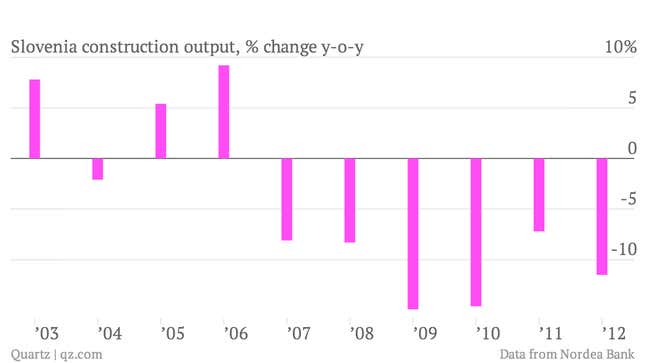

On the surface, it’s easy to compare Slovenia to Cyprus; both are small countries with problematic banking systems, and worrying about tiny economies bringing down the euro zone at the very least seems ridiculous. But their problems are quite distinct; Cyprus’s bloated financial system was closely tied to Greece, Greek sovereign debt, and investment in the Greek economy, and was crushed when the country defaulted. Slovenia’s problems look far more like the children of an asset bubble, particularly in construction.

In fact, that’s the most worrying piece of Slovenia’s debt puzzle. According to Morgan Stanley, about 18% of the corporate loans on banks’ books are for construction. About 60% of those loans are in danger of not being repaid.

That makes Slovenia’s problems look a lot more like those of Spain or Ireland, which both suffered from housing bubbles. ”As long as crisis management doesn’t get it completely wrong, it is more likely to be a, well, ‘normal’ case of crisis—maybe comparable to Ireland—and that would be bad enough,” writes Holger Sandte, an economist at Nordea Markets.

Policymakers have learned from the Irish case, where the government absorbed the non-performing loans of its two largest lenders. That inflated the country’s public debt to unseemly levels, and made a sovereign bailout unavoidable. Euro-zone leaders appear to have learned from that example in Spain, where the government created a bad bank, recapitalized it with debt guaranteed by the European bailout fund (paywall), and attempted not to put the burden of banking problems on the Spanish government. As in Spain and Ireland (before the government absorbed banks’ bad loans), Slovenian public debt is relatively low and the country is already on its way to creating a bad bank.

What’s next

On May 9, the Slovenian government will tell the European Commission how it plans to bring down its budget deficit and encourage economic growth. These plans could be the basis for deciding whether Slovenia needs a bailout program, EU economic and monetary affairs commissioner Olli Rehn told reporters on May 7. The country probably won’t get a sovereign bailout, though—at least, not yet. However, investors and policymakers worry that Slovenian politicians won’t be able to carry out the promised reforms, and that Slovenia will have to come begging for money down the line.

A possible alternative to a bailout—stricter EU oversight of the country’s economic reform program—may not be such a good thing either. “The decision as to whether or not to place Slovenia’s government under more onerous top-down oversight will be determined by the government’s reform agenda,” explains Eurasia Group analyst Otilia Simkova. “However, concerns do remain that such a step could precipitate a negative market dynamic: in effect pushing Slovenia closer towards a bailout despite the desire of the Eurogroup, and particularly the Germans, to avoid such an outcome.”